Dar Urtatim

Presents

Maghribi Women's Costume

From al-Andalus to Ifriqya

that is, from Spain to Tunisia

Click any picture for a more detailed view

There are few, if any, actual Maghribi garments remaining from the 7th through 16th centuries, the 1,000 year period generally covered by the SCA. We must compare images from art, written descriptions, and garments from the recent past which have survived to try to reconstruct what a "typical" Maghribi woman might have worn. Also, it should be noted that women in the city, women in the countryside, and semi-nomadic tribal women all dressed differently from one another, and, of course, there were differences based on class, religion, ethnic origin, and contact with other cultures, such as through trade. There is no way to reconstruct a single absolutely accurate outfit that represents what all Maghribi women wore, but there is enough documentation to create a workable semblance of general women's wear. |

Veiled and Masked Dancer 8 1/16" high Bronze, Alexandria Egypt, Hellenistic period, 3rd-2nd century BCE. in the Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Interior Clothes

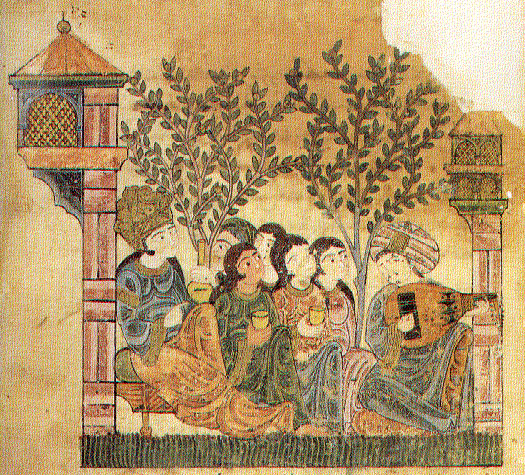

Maghribi woman of very high status in a garden with female attendents listening to Bayad play his oud 13th century CE From Hadith Bayad wa Riyad/The Story of Bayad and Riyad |

|

The neck opening was bound or had a rolled hem. In Antiquity, the neck-hole is a slit that runs horizontally along the shoulders just long enough to get the head through, or it could be longer and fastened on the shoulder, as in some more recent garments with ties or a button and loop. Later the opening appears to be a horizontally oriented narrow oval Later pictures show a vertical neck-slit in the front of the under tunic. Sometimes there is a thin cord to tie the neck opening, as in the 13th century illustration of the woman in white. The illustration from the 16th century shows a button at the top of the front neck opening--below right. |

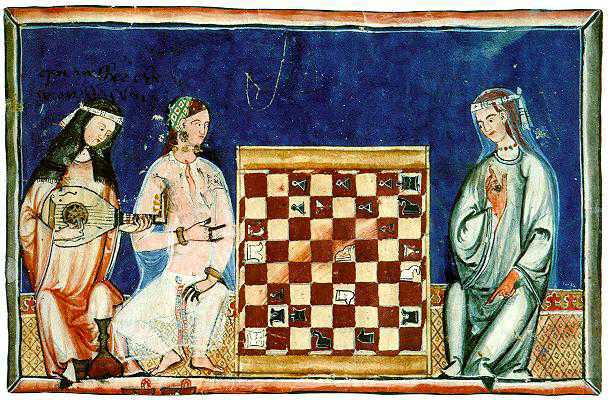

Outer TunicaOuter tunics were wool, linen, cotton, or, for the wealthy, silk. Art from before the 17th century consistently shows the fabric as solid colored, not brocaded or embroidered, in the Maghrib.As with the kamiz, the neck opening of the outer tunic was bound or had a rolled hem. Again, in Antiquity, the neckline ran horizontally along the shoulders just long enough to get the head through, or it could be fastened on the shoulder, as in some more recent garments with ties or a button and loop. In many medieval pictures, there is a round hole just big enough for the neck. Is it just big enough to get the head through or is there a slit in the back or along a shoulder that isn't illustrated? The painting from the 13th century shows aristocratic women with gold edging on their tunic necks and cuffs and gold Tiraz bands on their upper sleeves, indicating their status as aristocrats or people important to the government--above. Other examples in paintings seem to show the binding as matching the body of the garment. Sirwal/Serouelle or "Underpants"The lower body was covered by long pants, sometimes just as sheer as the undertunic and/or made of fabric matching the outer tunic (as in the two paintings from the 13th C.--above). Also quite often they are both painted and referred to in literature as being white - either linen or cotton. They have relatively straight legs and are wide at the waist where they have a drawstring, which is visible in the painting of three women above. They generally extend to the ankles, or are even a bit longer, pooling at the ankle. During the 15th and 16th centuries, sirwal legs may be bound around the calves, as in the picture at the right. I'm not clear if this represents a long narrow wrapper wound around the lower leg, socks/stockings/hose with the sirwal legs tucked in, or a separate leg piece, somewhat like gaiters. Vestiges of this covering remained until the early 20th century among some groups in the Maghrib. [insert modern picture here] |

FrimlaWhen the frimla developed seems to be unknown. It would not be visible when out of doors, but was part of visible indoor wear by the early 16th century. The only surviving examples I've found date from the 19th and 20th centuries, but it is clearly visible in the illustration from the mid-16th century--on the right. It is a combination of a sort of vest and a forerunner of the bra. In order get some idea of how it was made, we can look at those that have survived from the 19th century. |

by D. Ghisi, XVI Century Andalusian woman in indoor dress, wearing frimla, two short tunics, serouel, and hat |

HeaddressSome sort of cap or headscarf was worn on the head indoors, but it was not necessarily very covering. It could be a short rectangular scarf held on with a filet or headband, something like a coif, a "pillbox" hat (especially in Mamluk Egypt), or small almost flat cap similar to a yarmulke.

On an up-swept hairdo a woman might wear a chased or pierced metal cone, as in the 16th century picture at the left. Although I have seen no documented examples from before the 17th century, some hair cones from the 19th century are in museum collections, such as the one on the right. Sometimes women wear a small hat, reminiscent of a coif, but shaped a little differently - I'm just not quite sure how, as in the painting of three Andalusian women--above. Most common, however, is a simple veil covering the head and hair and held in place by a filet or narrow woven band. Several varieties are shown in the two 13th century paintings above. A hat with a brim that is narrow at the head and wider at the top appears to have been common in 15th and 16th century Andalus--above right. |

JewelryUrban merchant and noble class women do not generally wear vast quantities of heavy jewelry in the art I have seen. Large heavy ankle bracelets are sometimes seen. They are just another way to display one's wealth, and are sometimes reserved for ceremonial and festal occasions--that is, they are not "slave anklets". Women also wear earrings, sometimes large hoops with smaller bits of metal or gems dangling from them. A woman may also wear a necklace, usually just a single one, bearing in mind that the women represented in art are generally urban and associated with important households. Several necklaces have survived - the neckband is a mixture of gold beads, pearls, and gem stone beads. There is often a rather elaborate, but not large, gold pendant in the front, inlaid with jewels and pearls The idea that women wore massive amounts of jewelry and coins on their clothing or accessories comes from the display tribal women from the countryside have made in recent times. I have no idea how old this tradition of more-or-less wearing her dowry is. Until recently many women wore large amounts of jewelry in the form of fibula with chains and pendants, headdresses with coins and gems, and elaborate necklaces, as well as bracelets, anklets, and earrings. However, I have not seen any art that represents tribal or country women wearing masses of jewelry from between 600 and 1601. Jewish StylesI haven't done much study of these, but they would be only a little different from those of the Muslim population. Jewish women wore a veil/wrap in public much like the izar of Muslim women, as it was part of their own culture. Occasionally there were edicts specifying that Jews must wear certain colors or certain garments, but until the Almohads these were sporadic and not enforced. Because of Christian persecution in Spain during the Reconquista, there were several waves of Jews fleeing Europe to seek asylum in al-Maghrib. They brought with them some European fashions. Interestingly, until early in the 20th century, Jewish women in Tunisia were still wearing sideless surcotes for ceremonial and festive wear.  19th c. Tunisian Jewish woman's sideless surcote from Max Tilke, Costume Patterns and Designs Ottoman StylesA gomlek (a white shift), a zibin (later called hirka) (a colorful thigh length undertunic fastened down the front), a colorful kaftan (later called entari) (an ankle-length robe open down the front), a yelek (a hip-length jacket/vest for men and women), knee-length pants for men and ankle length narrow-ankled shalvar for women are 16th century Ottoman Turkish clothing. But Ottoman garments were not worn in Egypt or al-Maghrib in the 16th century. And big baggy "harem pants", commonly thought of a "typically" Middle Eastern, are not SCA period even in Ottoman Turkey. The Ottomans conquered Cairo Egypt in 1517, essentially putting an end to the Mamluk dynasty. But there was little Ottoman influence on clothing in Egypt during the 16th century, as only one garrison of Janissaries was sent from Istabul. And it wasn't until the very late 16th century that the Ottomans arrived in what are now Tunisia and Algeria; and they did not invade Morocco. Small units of Janissaries, Ottoman troups, were eventually stationed in a few cities in the coastal Tunisia and Algeria. But there were few of them compared to the mass of the indigenous population, and Ottoman clothing styles were slow to influence the regional costume. Thus, Ottoman garments or Ottoman-influenced styles are not Maghribi for SCA purposes. For some information about Ottoman Turkish clothing, see Ottoman Women's Clothing, late 15th to early 17th century and some annotated links to other websites with some Ottoman information. |

|

A look at 13th Century Andalus Back to the al-Riyad, the Courtyard in Dar Urtatim Back to the Front Hall Directory at Dar Urtatim Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Additional information?

You can write to me here. |