Dar Urtatim

|

|

Textiles were made for many purposes, of many different kinds of fibers, and in an amazing array of techniques in the Near and Middle East. Linen and wool are native to the whole region, cotton was grown in Arabia and the Levant, while silk was first imported from the Far East, then produced locally. The dyes of the region include indigo for blue and kermes and several other sources for brilliant reds.

For ordinary domestic consumption cloths were woven of linen and wool, and cotton in a few places, such as Yemen. Sometimes these were embroidered or ornamented with other techniques. They were used for clothing, mattress and pillow covers, rugs, wall and tent hangings, and yet more purposes. These were generally produced in home or village by women. A multitude of methods produced accessories such as socks in techniques such as naalbinding (also called needle netting), knitting, and sprang. Various cords were created by spinning, plying, braiding, and plaiting. Nomadic women wove tent bands of goat and camel hair. They also produced hangings for the tent's walls and cushions and rugs for the floors in various knotted and cut pile techniques, soumac, and other supplementary weft techniques. Unfortunately, few of these "humble" items survive. What have been preserved more often are the elaborate and luxurious fabrics produced in specialized workshops for the caliphs and governors of various dynasties, from Central Asia to Andalusian Spain, and given as gifts to people important to the rulers. These are often of silk in complex brocade, satin, velvet, and tapestry weaves. Most often the products of these workshops were wall hangings and rugs, as well as some garments made of silk brocades and velvets whose use was restricted by law to caliphs, governors, and those receiving special rewards from the caliphs. Textiles discovered in ancient sites in the last couple hundred years were cut up so more pieces could be sold to collectors and museums at first. They were often found by "grave robbers", not archaeologists. There was no documentation on where they were found or how they were disposed in situ. Thus sites were not properly excavated and fabrics were damaged and much information lost. This explains why so many fragments in museums are individual motifs or a repeat or two of a pattern often cut in a circle or rectangle. This is unfortunate as we can't always tell exactly where a textile is from; sometimes we only know general ideas of time and place by analyzing the decorative styles and textile techniques. Nor do we always know whether the fragment was part of a garment, a hanging, a pillow cover, etc. If a decorative band was on a plain linen garment, frequently the band was cut out and the remainder of the garment destroyed, which explains why so many Egyptian tapestry woven bands and roundels appear in museums as isolated pieces, matching sets often separated and spread through several museums.

The examples on this page are from:

|

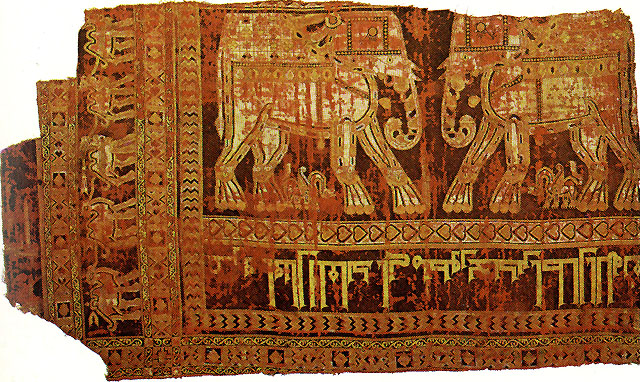

Ninth Century

|

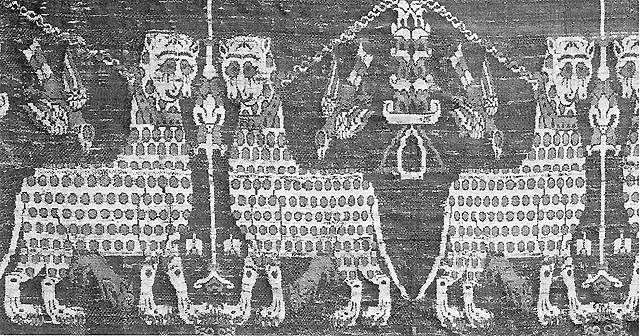

Tenth Century

|

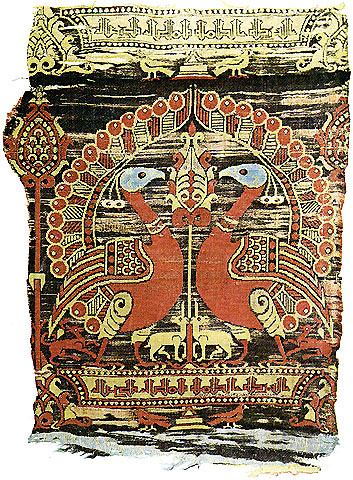

Eleventh Century

|

Twelfth Century

|

Twelfth Century

|

Twelfth Century

|

click on image to see a larger version

Thirteenth or Fourteenth Century |

Al-Riyad, the Courtyard at Dar Urtatim Questions? Comments? Suggestions?

You can write to me here. |

all text this page copyright 1999, known in the SCA as Urtatim al-Qurtubiyya bint 'abd al-Karim al-hakim al-Fasi