Ottoman Women's Clothing

Note that this page is not complete; i'm continually adding and improving it

for example, I 'd like to replace the 17th c. pictures with 16th c. pictures, if i can find suitable ones.

Paintings and illustrations of Ottoman men are commonplace and easy to find. For example, the entire Suleyman-nameh, an 16th century illustrated book on the life of Sultan Suleyman, includes no Ottoman Muslim women and only a few non-Muslim women from within and outside the Empire. Additionally, the vast majority of surviving garments, not to mention the armor, in the Topkapi Saray from SCA period were worn by men. This means there is far more SCA-period information available for men than for women.

Because of the difficulty of finding SCA-period illustrations of Ottoman women, i have gathered a selection here to illustrate that typical garments of an Ottoman Muslim woman living in a major city. Additionally, because of limited illustrations, i have included some from the 17th century which show clothing similar to that worn in the 16th century.

Here is my take on 16th century Ottoman women's clothing. A woman wears multiple layers of garments, depending on where she is, the weather, and the formality of the situation. In the harem, where almost no men will see her, a woman may wear her undergarments plus one zıbın. In a formal situation she may also wear four layers, the topmost layer being a coat of brilliant elaborate silk fabric. Out of doors she wears about four layers of garments, the topmost a muted colored wool coat.

As you can see, the outfits are quite attractive, and there is no reason why a woman won't look lovely dancing in an SCA-period outfit, rather than a 19th c. or modern fantasy outfit.

Basic Women's Garments

Note that ş in modern Turkish orthography is pronounced "sh"

gömlek -- sheer white under tunic

don ----- soft white under pants (optional)

zıbın --- short under jacket

tarpuş - [tar-push] small cap

şalvar - [shal-var] trousers

kaftan -- basic fitted coat

yelek --- short outer jacket (optional)

kaftan -- loose ceremonial coat (optional)

....... - small sheer white "veil" on back of head

ferace -- [fer-ah-jeh] woolen outer coat (optional)

yaşmak - [yash-mak] several scarves covering face and neck

Those marked optional are not necessary for one's very first SCA outfit.

This is not a comment on their necessity for women in the 15th-17th centuries.

|

Under Layer

Under tunic Under tunic

Gömlek - more or less goomlek (oo as in moon).- This is the basic undergarment, a sheer white tunic that pulls on over the head, with a long slit in the center front.

I know of none that have survived from the SCA-period Ottoman Empire. In art, there is no complete picture of a woman's gömlek, for reasons of modesty. The hem falls to mid-calf, or sometimes to the ankle. The "skirt" is quite full. Usually the sleeves are voluminous and quite wide at the wrist, draping without drawstrings or ties. The fabric is quite sheer and there appears to be embroidery on or along the seams

Since we are not certain what they were made of "in period", i use white cotton batiste, which is a very light sheer cotton. One could also use handkerchief linen as sheer as you can fine, or lightweight china silk/ silk habotai. I recommend cotton or linen for their washability and functionality, particularly in dealing with bodily moisture. If you plan to wear this in hot humid weather, i recommend linen, which is cooler than cotton. White wool might have been used in winter. It is very cold in a stone house with no central heating in Eastern Europe or Anatolia in winter, and some men's wool gömleks survive from later times.

I suggest using the pattern for the 14th century Persian pirihan and enlarging the sleeves

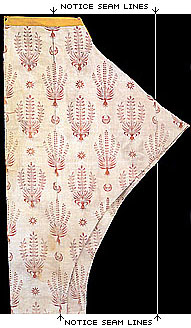

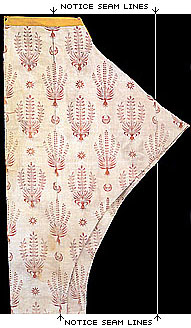

Extant Fourteenth Century Persian Pirihan/Kamiz

Rashid's Pattern

<-- Woman in White, ink and gold wash on paper, beginning 17th c. --- Woman in Red, European oil painting, mid-17th c. -->

both pictures from 9000 Years of the Anatolian Woman

Under pants: Under pants:

Don- It is clear from many paintings that women wore these underpants. The visible şalvar are quite often of elaborate expensive fabric, which one would want to protect from soiling. I have found a photo of one pair of don, which is made of a silk and cotton fabric, mostly sheer and with a couple opaque satin stripes.

These appear to be about upper or mid calf length, but some paintings show women in soft, loose, ankle-length don, so i would say either is a possibility. Choose the length based on your comfort levels and situation of use.

I make mine of white linen, but cotton is also a possibility. For reasons of comfort, I recommend against silk, but i have heard that some folks have success with china silk/habotai in light weights. I find that if i am perspiring, silk is not effective.

Photo credit, below...

- Foot Covering

- Indoors, when not barefoot, women often wore sock-like foot coverings that extended up to their lower or mid-calf. These were made of soft yellowish leather or woven cloth - often elaborate silk brocades -.

Going to the bath (hammam) a women wore wooden nalin, flat slip-on sandals elevated by two tall wooden crosspieces, rather like Japanese geta, often with elaborate chipcarving and ivory inlay. They had one or two straps around the instep, worn with leather socks or bare feet.

- Head Covering

- Women always wear some sort of cap - a simple pillbox shape is appropriate for the 16th century (see Codex Vindobonensis pictures, below). The tall narrow cap in the pictures above are 17th century.

- Jewelry

- Jewelry is modest in size and quantity, NOT like what ATS dancers wear. All that ethnic jewelry, as lovely as it is, just isn't right for Ottoman outfits. Gold jewelry is what is desirable. Silver is for those who can't afford gold. Since i can't afford all that gold, either, i wear gold washed jewelry and brass bracelets. *Small* gold hoops, a small simple necklace of gold, gold bracelets are appropriate. Pearl drop earrings and long strands of small pearls can also work.

Second Layer

Fitted Underjacket Fitted Underjacket

Zıbın (both "i"s are very short)- This is a short tight coat, cut like the kaftan (see third layer), but more fitted in the body, with the hem about mid-thigh length to above the knee. There are several sleeve possibilities. It is worn over the gömlek and under the kaftan.

The example at the left does not actually have an oddly shaped "window of opportunity". First, the "artist" was an untrained European, so his drawings leave something to be desired in terms of verisimilitude. Additionally, it is clear in other paintings and surviving garments that the front is cut straight down, but is pulling apart across the fullness of the bust. In this case, the garment has a small circular neckline right at the base of the neck.

The bright red zıbın above right had buttons from the neck down, but is left open across the bust. It also appears to have a small standing collar. It is hard to tell about the zıbın on the Woman in White - it may have a fully buttoned front or it may have a rounded V-neck.

If cut "correctly" it can provide bust support with no modern supplements. This was not done "in period", but it's possible.

The same garment names are used in Turkish for centuries, yet the garment shapes change radically. This word is used for a couple different garments in the 19th through 21st centuries, quite different from that of the 16th c. Several scholarly sources i've read call it hirka or chirka (Encyclopedia of Islam, 8th ed., for example), but the word for it in the 15th and 16th centuries was zıbın. I have noticed it called a "cardigan" in some modern Turkish writing in English, but in my experience a cardigan is knit, whereas these garments are of woven cloth. The Turkish writers are making a literal translation to its modern meaning.

- Pants / Trousers

Shalwar also written şalwar, salvar, or şalvar

- These are narrow at the ankles and widen as they go up the thigh. Quite a few have survived from the late 16th and 17th centuries. şalvar are often made of the same kinds of fabrics as the kaftan, but they should NOT match.

In some of the accompanying pictures you can see that some şalvar are made much longer than the actual woman's leg, and of very soft fabric that pools around the leg.

Big poofy so-called "harem pants" are *way* out of period for the SCA. Please, i beg of you, don't make them or wear them. I'm groveling, please, don't do it.

Third Layer

Fitted Long Coat Fitted Long Coat

Kaftan- This is the basic garment worn by both men and women. It is an ankle length "coat" that buttons down the front. Most often it has a high round neckline in the 15th and 16th centuries. It is often leaft unbuttoned from sternum up and from waist down. It is somewhat fitted in the body but has no darts or tucks, no curved or shaped seams. It's all done with straight seaming. To accommodate the hips it has side gores. To accommodate the bust it has somewhat large underarms gussets.

Entari, also written enteri, anteri, antari, etc., is the name for a dervish's coat and an 18th century name for a kaftan, but not any other 16th c. coat.

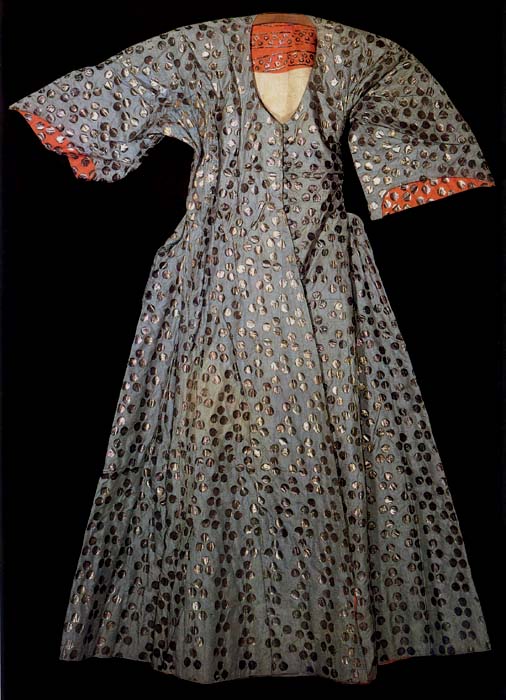

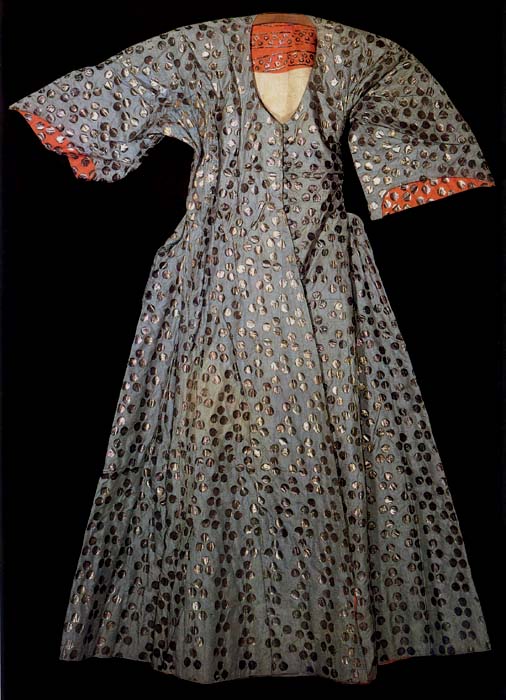

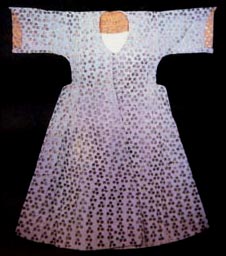

This late 16th, possibly early 17th, century medium-light blue kaftan has decorations of silver leaf attached to the base silk with an adhesive. On the outside, and in the sleeves, notice how groups of three circles are arranged to form çintamani-like triangles, with a rather different pattern on the salmon-orange-colored neck facing.

Notice the cut-away shape of the hem of the "wing" sleeve, made to be worn over a zıbın with long tight sleeves.

The V-neck on this kaftan is unusual and not typical of most kaftans, which went all the way up to the bae of the neck.

Left picture, from Topkapi Textiles; right picture from 9000 Years of the Anatolian Woman

- Fitted Outer Jacket

Yelek

- This is a very short coat worn over the kaftan in cold weather. It gets pretty darn cold in what is now modern Turkey in the winter. It is shorter than the zibin - crotch to mid-thigh length - and a little less fitted than the kaftan so it will fit over it. It has sleeve variations. It is possible that it was not worn in the 16th century.

Note that the 19th-20th c. Levantine yelek is a very different garment.

- Head Covering

- A veil of sheer white cloth is worn over the cap and hangs down the woman's back. I don't know of what they made theirs, i suspect linen. I use white silk chiffon, but sheer white handkerchief linen, sheer white cotton batiste, or lightweight china silk/habotai would also work in the SCA. I anchor mine on with pearl headed pins. As you can see in the pictures from the Codex Vindobonensis below, a fillet (like a narrow headband) is used to hold the veil onto the cap.

Ceremonial Layer

- Loose unfitted Coat

Kaftan

- This sort of garment is worn by men and women in formal, ceremonial situations, such as religious or state events. It is ankle length and unfitted, large and voluminous. It has the cut-away "angel wing" sleeves. Made of rich luxurious fabric, such as pure silk brocaded and cut velvet, quite often red with metallic gold, they can be lined and even trimmed with fur for warmth in winter.

- Head Covering

- The cap with a veil.

- Foot Covering

- Little slip-on flats or low boots are worn over the brocade or soft leather socks

Outdoor Layer

Overcoat Overcoat

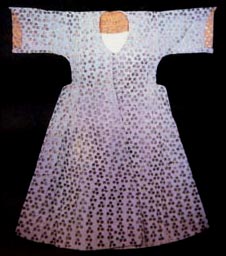

Ferace (ferajeh)- This is a large loose coat worn over all the other garments of layers one through three. It was usually made of wool and in muted modest colors, such as dull medium blue, grey, brown. In period they have modest simple round neckholes. Some summer ferace were of silk and had short sleeves. The ferace often had slits over both hips so the woman could put her hands inside to keep them warm in winter or to access a pouch.

Muslim women could choose from a range of colors for their ferace. Jews and Christians had a choice of very very dark indigo or black.

Note that it is only beginning in the 18th century that ferace have huge broad collars hanging in back to the waist or even to the hem.

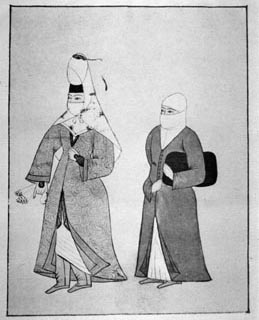

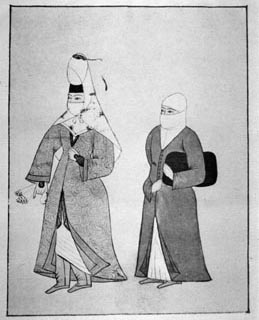

<--- late 17th century drawing ----- two 16th century examples --->

- Head Covering

Yaşmak (yashmak)

- This is a scarf or set of scarves worn over the cap and covering the lower face and neck. The black-and-white picture on the left is from later in the 17th century, as evidenced by the hat that is wider at the top than the bottom, covered by the yashmak.

- Eye Mask

Peçe (peh-cheh)

- This horsehair mask, often black, covering the upper face, appears in some pictures.

- Foot Covering

- Women often wore sturdier soled boots over their socks and shoes.

130 Years of Ottoman Women in European Art |

|

Drawing of a serving woman, circa 1490

Giovanni Bellini

drawn from life when the highly trained and famous Italian Renaissance artist was in Istanbul |

|

|

|

|

Codex Vindobonensis 8626

Believed painted between 1586 and 1591

by an unknown south German artist in the entourage of Bartolemeo di Pezzana, ambassador of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II to the Sublime Porte.

Now in the Austrian National Library, Vienna |

|

|

|

|

|

1618

Album leaves purchased in the bazaar from Englishman Peter Mundy's journal of his trip to Istanbul

|

| The woman on the left wears white gömlek and don (which appear to be of very soft material), a blue patterned zıbın (see the sleeves), an orange kaftan with short "wing" sleeves, a dark blue yelek with no sleeves, and yellow leather slippers. |

The woman on the center-left wears no apparent gömlek, an orange zıbın, something with blue patterned sleeves, stiff blue brocade şalvar, a dark gold kaftan with short "wing" sleeves, and white bootees. |

The woman on the center-right wears white gömlek and don (which appear to be of very soft material), a short-sleeved patterned zıbın, and bare feet in nalin. Embroidery is visible along the seams of the gömlek, the gömlek skirt and sleeve hems, and the lower hem of the şalvar legs. |

The woman on the right wears a patterned yelek over her plain kaftan. The front hem of her zıbın is peeking through the opening of the kaftan above the white of her gömlek. She wears patterned şalvar and sock-bootees of a different brocade. |

|

|

Illustrations on this page from various sources, including:

Section C. Seljuk and Ottoman Periods, pp. 190-295

by Dr. Filiz Çagman and Dr. Banu Mahir

9000 Years of the Anatolian Woman

Turkish Republic Ministry of Culture General Directorate of Monuments and Museums

Istanbul, 1993.

ISBN 975-17-1186-X

"Fashion at the Ottoman Court: The Topkapi Museum Collection",

Section I, Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Women's Fashion at the Ottoman Palace, pp. 4-17

by Hulya Tezcan, translated by Sungur Savran.

The photo of the burumcuk chakshir is on page 14.

Published in: P Magazine Art Culture Antiques Bi-annual, Issue 3, Spring-Summer 2000

|

Fabric

FIBERS

For the gömlek, use pure white fabric, or off-white/ivory if you prefer. Cotton is good, especially batiste, as is handkerchief weight linen. In this case habotai/china silk would have a suitable weight. I think that undergarments would more likely have been cotton or linen, and that cotton and linen serve the function better than silk at dealing with bodily moisture. In the winter men wore ivory wool gömleks - i don't know if women did, too.

For kaftans (and zıbıns and yeleks), silk is best, of course:-) I buy dupioni when it's on sale (between US$7.50 and $10 a yard [that price was a long time ago...]) and mostly i get the 54" wide stuff. I realize the slubby fabric would not have been used as outer fabric, but it's what i can afford and still be silk, and it has the right hand. I get both solid color and shot silk. Shot silk has one color in the warp and one in the weft - the surface is the more closely set color, while the other shows in the folds, lending an iridescent quality. Most habotai/china silk is too thin for outer fabric, so I use it for lining because it's fairly inexpensive.

I also buy some mostly-cotton upholstery fabric when i find it on sale with woven Ottoman-oid patterns. I even managed to score some that was a copy of an actual late 16th-early 17th c. Ottoman fabric! Such fabric needs to have a soft hand. If it's stiff, it will work for a khaftan - the outermost formal "coat" - but it won't work for the antari, which needs softer fabric for easier fitting and better drape.

These multicolored woven upholstery fabrics available at the typical fabric store are commonly called "brocade" or "tapestry", but are neither. They are actually Jacquard woven and because of the Jacquard weaving process, the fabrics tend to be thicker and generally much stiffer than period brocades and the threads themselves are quite often thicker as well. Since true brocades are out of the price range of most SCAdians (starting at a few hundred dollars per yard and going up into the multi-thousands of dollars per yard) we are generally forced to buy Jacquard simulations

Damask weaves are also suitable, although i haven't seen as many of them in Ottoman garments. Damask fabric usually has the same color warp and weft, which because of the way it is woven, with long floating threads, has a clearly discernable textured pattern. There are also Damasks with one color in the warp and a different one in the weft - in this case the pattern on both sides will be the same, but in opposite colors - for example, one side could have blue flowers on a yellow ground while the other has yellow flowers on a blue ground.

I also buy a few printed cottons if they have a very Ottoman pattern and gold metal stamping. These are best lined with silk and best worn with silk over them, because otherwise the cotton will stick to the other garments.

PATTERNS

There are several chief characteristics of Ottoman fabrics. One, they are highly formal - no random scattering of motifs. Second, the motifs are usually on a large to very large scale. The patterns in some period Ottoman fabrics only repeat 1-1/2 times from shoulder to hem on a tall man's garment! Third, the patterns are often arranged vertically, such as tall wavy lines of highly stylized flowers.

Common motifs include pomegranates, carnations, tulips/lilies, cypress trees, crescent moons, abstract patterns arranged in ogee forms (sort of vertical ovals with pointed ends). One very distinct pattern is çintimani (pronounced chin-tah-mah-nee) - in the individual motif, three circles are arranged in a triangle which is frequently accompanied by two short wavy lines. The significance of this is uncertain - there is speculation that it is a Central Asian pattern, similar to one seen in Tibetan fabrics. The woman seated on the far left of the first Codex Vindobonensis picture has a kaftan with this pattern in white on blue.

COLORS

Fabric for kaftans, zıbıns, and yeleks would make use of prestige colors like kermes red, a rich cool red. In surviving garments and fabric fragments there is much more red fabric than any other color, often with golden-yellow designs, sometimes with other accent colors. There's a much lesser amount of indigo blue (which can dye anywhere from very pale to nearly black). Then there's some amazing fabric that has a nearly black ground with a fairly large pattern of sinuous vines and flowers which are red, yellow, blue, and white. There are also some garments of dull medium green (greener than olive drab, but not much), and some using brown, usually partnered with white. Metallic gold threads were often woven into the pattern.

Linings tend to be olive green, teal blue, red, or golden yellow - NEVER matching the outer fabric.

Feraces were usually of wool in a modest color. Muted blue, grey, or brown are more likely than light or bright colors, since in public modesty is essential, and pale or bright colors are considered less modest. Christian and Jewish women could only wear black or dark dark indigo feraces.

Questions? Comments? Suggestions?

You can write to me here.

|

This page first published on 02 May 2005

and copyright Urtatim al-Qurtubiyya bint 'abd al-Karim al-hakam al-Fasi

|

Under tunic

Under tunic

Fitted Long Coat

Fitted Long Coat

Overcoat

Overcoat